Ruby Ling Louie

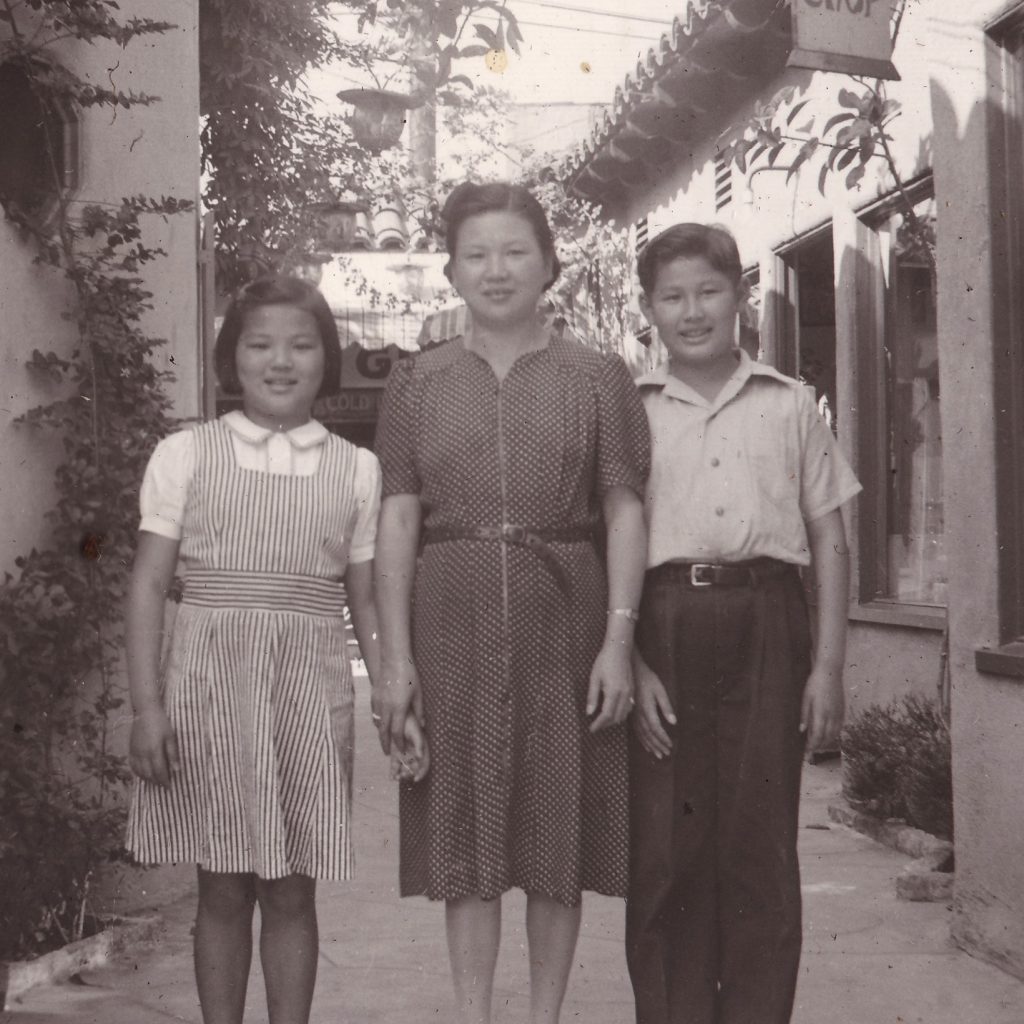

Ruby Ling Louie grew up around her parents’ businesses in China City.

About

Written by Andrew Jung

Ruby Ling Louie was born on April 11th, 1931 in Chicago, Illinois. Traveling seems to be a part of the Ling family tradition. Her parents came from a village called Tsingtien in Chekiang Province. Her mother was the eldest of seven children and her father was the youngest of four brothers.

Trying to find a better life for his family, Ruby’s adventurous father traveled to Seattle, then to Chicago and finally settled in Los Angeles. An industrious entrepreneur, Ruby’s father participated in the World’s Fair in various cities.

In San Diego that the Ling family discovered the auspicious weather offered by California and settled in Los Angeles with a curio shop in China City, which sold “scholar’s stone” carvings made by villagers from Chekiang.

Established by Christine Sterling, China City was created due to the success and the need for Chinese Americans in the burgeoning movie industry in Hollywood. As a young child, Ruby considered her neighborhood a multicultural environment. There were Italians, Russians, Croatians, French along with various Chinese immigrants.

Ruby helped work at her father’s curio store. As the youngest of four children, she was allowed the luxury of running around and visiting her friends as opposed to her older siblings who had to constantly mind the store. In school, Ruby attended Alpine Street Elementary and later attended Belmont High School. She laments to this day how her Central Junior High School was closed down because she feels that if it had remained open, many of the different ethnic communities in Chinatown could have further intermingled. Ruby fondly remembers her China City; as a multicultural and multiethnic community where “honest immigrants” had an entrepreneurial spirit and creatively worked to better their families’ lives.

During World War II, the war in Asia prevented Ruby’s father from continuing to resupply his three shops with curio and art goods. After consulting with a family friend, Ruby’s father decided to start a restaurant business. In 1942, Ling’s Café opened in Long Beach, California. There the family made “good American Chinese food” for everyone. Ruby, being the youngest, served as the out-order clerk while her brother and sisters worked as waiter/ess. After graduating high school, Ruby continued to work in her parents’ restaurant. Trying to find more to her life, she luckily was advised by a counselor to attend Long Beach City College. To this day, Ruby advocates for city colleges as an incredible source of education for all peoples. Ruby attended Long Beach City College for almost five; interestingly, she also set the record by accumulated at that institution with 62 credits. Eventually, Ruby attained a Bachelor’s of Arts degree in general elementary education at UCLA, where fortunately pioneering librarian, Frances Clark Sayers, encouraged her to become a librarian. Ruby entered Carnegie Tech in Pittsburgh for her Master’s degree, and eventually obtained a Ph.D. from the University of Southern California that helped her to establish the first public library in the L.A. Chinatown community. Along the way, she married Hoover J. Louie, a member of one of the founding families of Los Angeles Chinatown, where they raised their two children and still live today.

Features

Interview with Ruby Ling Louie; March 28, 2008

WG: Dr. William Gow

RLL: Ruby Ling Louie

RLL: Intermingled. The Chinatown people sort of like the nuances that we offered in China City because we were very compact, you see, and all the movie stars came first to us, and so they’d come running down. And then there was an older lady who would sell gardenias. She had a wonderful gimmick; she had us young people going out in a little box, and she commissioned us to sell single gardenias, and she herself was watching around. I can still hear her “Gardenia nice,” you know. Her English was limited, but she had… entrepreneur people were really in my world there that I saw of all kinds. But the whole composition of China City as you look back at it, it really was a… it represented different regions of China where you see Chinatown were all, as you say, the Toishan. They were all united. They all knew what they wanted to do. They had been fighting the adversities of ethnicity. We were just all loose people that just, you know, doing the best we can, and one of the greatest Chinese characteristics I must admit of that time is every immigrant, there was a character that, as my brother verified, and he’s a lawyer, they were honest immigrants. They did not want to have relief. It would be a shame to go and say, “I don’t have enough money for the food for my family.” And yet they did not go into criminal activities, and so it forced them to think creatively to do anything. And I think that’s the first time I saw more… China City had more, what do you call it… I had a word for it before, but set up stores outside of the stores. I mean the-

WG: A stall?

RLL: Yeah, the stall kind of thing, the thing you see now that’s prevalent with the Hispanics, you know. They just extend their store out to the door and then they open… and the Vietnamese do that. The new immigrants have to learn to be creative in order to provide means for their families.

WG: So, when you say that the people of China City were maybe not from Toishan but from different places, do you remember specific examples that you could tell me of families and where they were from? Can you… do you remember any of that? Like family from here or family from there? Can you tell me where some of these other…

RLL: Not so much. Such a mixture. No, you’d have to check…did Esther tell you any? Did she meet any other…She couldn’t, huh?

Ruby Ling Louie on China City

Ruby Ling Louie in China City

In 1936, we came to Los Angeles, and [my father] looked where he could open a store. Where the connection is of finding China City is still unknown to me, but he [went] there. Jake Su and Dorothy Su at the Flower Hut were already established there, and my dad, being clever because he had not enough money with four children to provide, suggested, “Could I set up a table and put up some of my goods?” We sold successfully enough, and he negotiated to open up a store up on Spring Street, Chekiang Importers.

My older sisters had to watch the stores, but I, the youngest one, was the freest, so I was able to visit the other children. We really had a community of children because most of the families were larger and all related. I could help with the store when they absolutely needed it, but I was out with Choi Lan in her father’s basketry store. We were playing dolls and eating minced ham sandwiches. We were having a fun time.

Multicultural is a term I want to use for the Chinatown that I grew up in as a youngster. They think only the Chinese were here. We actually replaced the Italian group. They hadn’t all left yet. They’re all gone now, but my mother-in-law bought her house from an Italian because we couldn’t buy the houses then.

China City did have, uniquely, a variety of other than Chinese people participating because the renter of China City, Christine Sterling, and her managerial staff wanted some variety. It was a very wonderful community, perhaps because also the staff was so inspiring. They liked the idea that they were helping the children of all immigrants.

China City was made up as a temporary effort because The Good Earth had been a successful film. Christine Sterling was going to have her international theme park. She was successful with the help from her influential friend, Harry Chandler with the newspaper. Imagine getting access to the media. No Chinatown community ever had the amount and consistent publicity that China City had in those days.

Tom Gubbins and Christine Sterling truly were the two Westerners who actually established it. One established it, the other promoted it. They believed that Chinese culture needed to be exposed to the mainstream world, and that’s the way they envisioned this presentation. That’s how they drew these people in.

Christine Sterling insisted that we wear costumes that showed our culture. Of course, sometimes you would feel it’s denigrating. I am American, why [do I have] to put that on? [But] it was a real attraction between doing that and the kung fu that Wong Loy did. You came to see a show, you came to eat things, you saw craft people making things. You could also have Mexican food here, then you have the wonderful China Burger.

The Chinatown people liked the nuances that we offered in China City because we were very compact. The whole composition of China City represented different regions of China, where Chinatown was all the Toishan. They were all united and all knew what they wanted to do. They had been fighting the adversities of ethnicity. We were just all loose people that just doing the best we can.

Summarized by Rionna Tsai (2021)